A Framework For Universal Principles of Ethics (2018)

by Larry Colero, Vancouver, Canada

If there was a set of universal ethical principles that applied to all cultures, philosophies, faiths and professions, it would provide an invaluable framework for dialogue. (Colero, 1997)

In 1997, Dr. Michael McDonald, Founding Director at the University of British Columbia’s Centre for Applied Ethics, suggested I write a short article for their website based on a checklist of principles I had compiled to help me as a layperson understand the fundamentals of ethics. To my surprise, that original three-part framework has now been used without revision by more than fifty organizations in twelve countries across five continents.

Governments, corporations, churches, schools, hospitals, professional associations, law enforcement agencies and the judiciary have used it to teach ethics, develop codes of ethics, assess ethical dilemmas and conduct research. As of 2018, the framework has also been included in a wide range of presentations, professional journals, textbooks and other educational materials, and reprinted by diverse faculties at nineteen universities and eight colleges.

When I wrote the article, I expected such a simplified explanation of an endlessly complex topic would be refuted, controversial or just ignored. None of those things happened and 21 years later I am still receiving requests to use or republish the framework.

Why has my attempt at a universal ethics framework been so widely used?

Ethical dilemmas rarely present themselves as such. They can involve us before we know it, or develop so gradually that we can only recognize them in hindsight, like noticing the snake after we’ve been bitten. An ethical framework can be used like a ‘snake detector’ to help us understand when danger might be present. A universally-accepted framework can provide useful warning signs when navigating the myriad mores of our global society.

At first glance, some of the principles may appear to be simplistic. They are meant to be more practical than precise, like multi-purpose gadgets in a ‘Swiss army knife’ approach to recognizing what is right or wrong (or in between) across virtually all cultures. In total, they are a guide to recognizing when situations might have ethical implications – a crucial first step. If these implications are never identified, it can appear to us that there is no ethical issue to prevent or resolve.

The principles are generic indicators, designed to stimulate and provide guidance to an active conscience. Unlike other kinds of principles which are absolute and constant, these are more like guidelines for situations where a precise answer is rarely possible. As such, they are not descriptions of rules, societal norms or values. Instead, they represent ethical factors that commonly need to be identified, considered, and applied with good judgement by those of us who strive to live ethically.

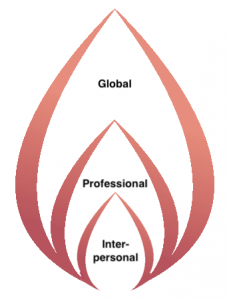

For many people, the most significant advantage of this framework has been its separation of principles into three types of moral responsibility. Those three categories are now called Interpersonal, Professional and Global Ethics. I chose to depict them in this update as a flame to illustrate their simultaneous interrelationship. They overlap like the typical colours of a flame, and the interplay between them is constantly changing. Any category may seem to disappear at times, yet each one remains as a potential with its prevalence dependent upon the circumstances.

Most of the principles are outcomes of the mother of all principles – unconditional love and compassion, which is expressed in various ways as The Golden Rulein virtually all faiths and belief systems. I chose to express this notion as the first principle in the framework, “concern for the well-being of others” which I believe is its essence. This guiding principle can be revealed and put into practice instinctively in many situations as an act of ‘love’. The person who expresses that love need not be able to explain their reasons (as I have attempted to do with the framework). The Golden Rulealone can often provide all the clarity they need to understand how they should treat others and put ethics into practice.

While there is some merit in the idea that we should follow our intuition and rely on our conscience or ‘inner voice,’ that voice is not always clear or objective. As our society becomes increasingly global, we face an ever-widening range of intercultural challenges, making compassionate instincts less dependable guides. We need to ask more than “does it feel right?” A framework like the one below can be used as a toolbox of checkpoints for diverse groups to find consensus on ethics, or to guide individuals on the never-ending path to ethical awareness.

A Framework for Universal Principle of Ethics

Interpersonal Ethics

Interpersonal Ethics might also be called morality, since this category of principles reflects general expectations of any person in any society, acting in any capacity. These are the principles we typically try to instill in our children, and expect of one another without needing to state the expectation or formalize it in any way.

Principles of Interpersonal Ethics include:

- Concern for the well-being of others

- Respect for the autonomy of others

- Trustworthiness and honesty

- Benevolence (doing good)

- Preventing harm

- Basic justice (being fair)

- Willing compliance with the law (with the exception of civil disobedience)

Professional Ethics

Individuals acting in a professional capacity take on an additional, formalized level of ethical responsibility. Professional associations’ codes of ethics prescribe required behavior within the context of a professional practice such as medicine, law, accounting or engineering. These written codes provide ethical standards and rules of conduct commonly based on the principles below.

Even when not written into a code, the principles of Professional Ethics imply duties and responsibilities commonly expected of employees, volunteers, elected representatives and many others in the workplace.

Principles of Professional Ethics include:

- Impartiality (objectivity)

- Openness (full disclosure)

- Confidentiality

- Due diligence (duty of care)

- Fidelity to professional responsibilities

- Avoiding potential or apparent conflict of interest

Global Ethics

Global Ethics was placed at the top of the flame illustration to suggest it as an evolutionary ideal to which humanity can ultimately aspire. It is the most controversial of the three categories, and the least understood. Open to wide interpretation as to how, when or whether they should be applied, issues related to these principles can generate emotional response and heated debate.

Principles of Global Ethics include:

- Reverence for life (in all its forms)

- Interdependence & responsibility for the ‘whole’

- Society before self / social responsibility

- Global justice (as reflected by international laws)

- Environmental stewardship

- Reverence for place

Each of us influences the planet simply by living on it. As we learn more about our human impact on the world, it is increasingly important for each of us to ‘think globally’ by applying the ‘precautionary principle’ (recognizing and respecting the unknown) to minimize our harmful impacts on Earth’s countless ecologies and cultures.

Influential or fiduciary enterprises such as governments, large corporations, or NGOs (Non- Governmental Organizations) take on an added measure of accountability. Responsibility comes with power whether we accept it or not, and one of the moral burdens of leadership is to influence society and the state of the world in a positive way. Global Ethics can inspire us to accept shared responsibility.

Co-existence of Principles

Many situations will never lend themselves to an easy formula, and these principles can only be used to trigger our conscience or guide our judgement. Principles often conflict with each other in practice, and some can trump others under certain circumstances. Here is an example of how principles can collide or override each other.

Let’s say you are a scientist working on a government project to study the effects of a certain chemical on human health. Over time, it becomes clear to you that your government’s intention is to use the chemical as a biological weapon. Since the project is top secret, you have a patriotic duty as a citizen and a professional duty as an employee to maintain confidentiality. (Trustworthiness is fundamental to professionalism.) However, if there was an opportunity to inform United Nations observers, then Global as well as Interpersonal Principles would likely justify divulging confidential information to save lives and protect the overall good of humanity.

Similarly, when judging if a corporation has been ‘socially responsible,’ we need to include principles of Interpersonal as well as Professional Ethics as prerequisites for corporate integrity. In other words, the company cannot be internally corrupt and deemed socially responsible at the same time. Contributions to charities and the like (benevolence) may be in the interests of society, but these actions lose significance if the corporation has not also taken responsibility to minimize any damage their business activities may cause to customers, employees and other stakeholders. (In this case, the Interpersonal principle of “preventing harm” would prevail.)

Universality versus Selective Application of the Principles

When these principles are applied selectively or only within set boundaries such as next-of-kin, countrymen, race, gender, and so on, that ‘cronyism’ effectively negates their value. For example, my mother was born in Sicily, which is also the birthplace of the Sicilian Mafia, a crime syndicate that has committed many despicable acts. Yet they have a rigid code of honour within their own ‘family’, trustworthiness is highly valued, and they have a strong (albeit perverse) sense of justice.

My aunt ran away from home at a young age and married into what she and her family described as “the Gypsy life”. Some of my cousins were trained to pick pockets, but they would never steal from me because I was part of the family. Limiting application of ethical principles in this way converts them from a universally virtuous path into an exclusionary code of conduct.

Apart from cronyism, there are contextual interpretations of the principles that many societies consider acceptable. For example, murder may be illegal but forgiven if the killer is taking another life in self-defense or to save others. Lying is considered wrong unless we tell an untruth to protect someone from harm. These interpretive variations sometimes cause people to conclude that ethical responsibility is entirely relative to personal beliefs or local standards and cultural practices.

This ‘moral relativism’ (the concept that no one can be wrong) is a dangerous assumption that relieves us of any responsibility other than what we choose to interpret in our own interests, what is prescribed by faiths or governments, our own values as an individual, or the local status quo.

Still, each of the principles can be embodied in different ways. Virtually all cultures value honesty, yet they can have different views about truth telling – as illustrated by Eastern vs. Western values for harmony versus being forthright. A person from Japan being polite to maintain good relations may be perceived by an American as deceitful, although that may not be the case at all. Both cultures agree in principle that deceit is unethical and trustworthiness is ethical, but misunderstandings can arise when that underlying principle is enacted in differing ways, reflecting traditional cultural practices that are based on conflicting values or virtues.

And so, morality cannot be distilled into a universally acceptable list of specific rules. The principles listed in the framework above can only describe commonly recurring patterns of ethical responsibility that our conscience can use as enduring landmarks in a wide range of situations.

How I unintentionally discovered this framework

I developed the framework before I had ever taken a course in ethics. After reading a little on the subject and attending a few lectures and conferences, I was struggling to understand how ethics related to my position as a (non-certified) professional in a large multinational consulting engineering firm. So I read some more and gradually put together this list of principles as a layperson’s ‘cheat sheet’ to help me recognize when and how ethics might apply to my own work, never intending to publish it.

As my career shifted into adult education, I began using the framework as a starting point for students to reflect on ethics before participating in case study discussions. I tested it in sessions with hundreds of adult students from diverse backgrounds, with opposing objectives, and at both ends of the political spectrum. While I am still not claiming that this is an ultimate or complete set of ethical principles, I can safely state that the framework has been a reliably versatile tool, with proven applicability around the world for widely diverse purposes.

Encouraged over the years by the number of other educators who reported success in using the framework, I eventually used it as the basis to teach business ethics at the graduate level at the two major universities here in Vancouver, then as the foundation of an in-depth online Ethics program for an 18,000- person transnational corporation. Up until that time, in every class or seminar, I explicitly asked participants for their concerns about any principles they thought inappropriate, objectionable or unclear, and I tested their understanding through discussion and case study dialogue.

I fully expected to revise the principles based on student feedback. But in spite of the original article also containing a request for feedback and “substantive comments”, only one addition to the original set of principles has ever been suggested. That missing principle, suggested by Richard Sieb in 2016, is the “reverence for life,” meaning all of life (including non-human).

As a pacifist, I instinctively supported what is sometimes called the “sanctity of life” as a universal good. However, after more than 20 years of testing the original framework with thousands of people from different cultures, faiths and professions, I was reluctant to add a new and untested principle. As well, one could argue that some cultures do not accept reverence for life as a principle at all, overriding it with culturally-specific virtues like honour, patriotism or reciprocity. In spite of this, after much reflection, I have now chosen to add reverence for life to this update as a Global principle because of its overall, wide-ranging importance.

I hope that this simple guide, discovered and published through serendipity more than twenty years ago, will continue to be of some value to future generations.

This document may be downloaded or printed for your own use, but written permission from the author is required before distributing it to others. To request permission to use the Framework, to access supporting educational materials (including a one-page handout of the principles) or to offer comments, please contact the author through www.larrycolero.ca